John Millei – Mediation in Three Acts

With Meditation in Three Acts, John Millei presents an extraordinary new body of work that both extends and radicalizes his previous oeuvre. For the first time, the artist turns explicitly to inner states of consciousness—not through narrative devices, but through a symbolically charged, abstract visual language. The three large-scale paintings that comprise the cycle are conceived as a cohesive visual unit, yet each one also stands powerfully on its own.

This synthesis of conceptual clarity, iconographic depth, and painterly presence lends the work both historical significance and notable value for collectors.Structurally, the series follows a trajectory analogous to meditative practice: from heightened awareness through the gradual release of cognitive control, culminating in a state of contemplative immersion.

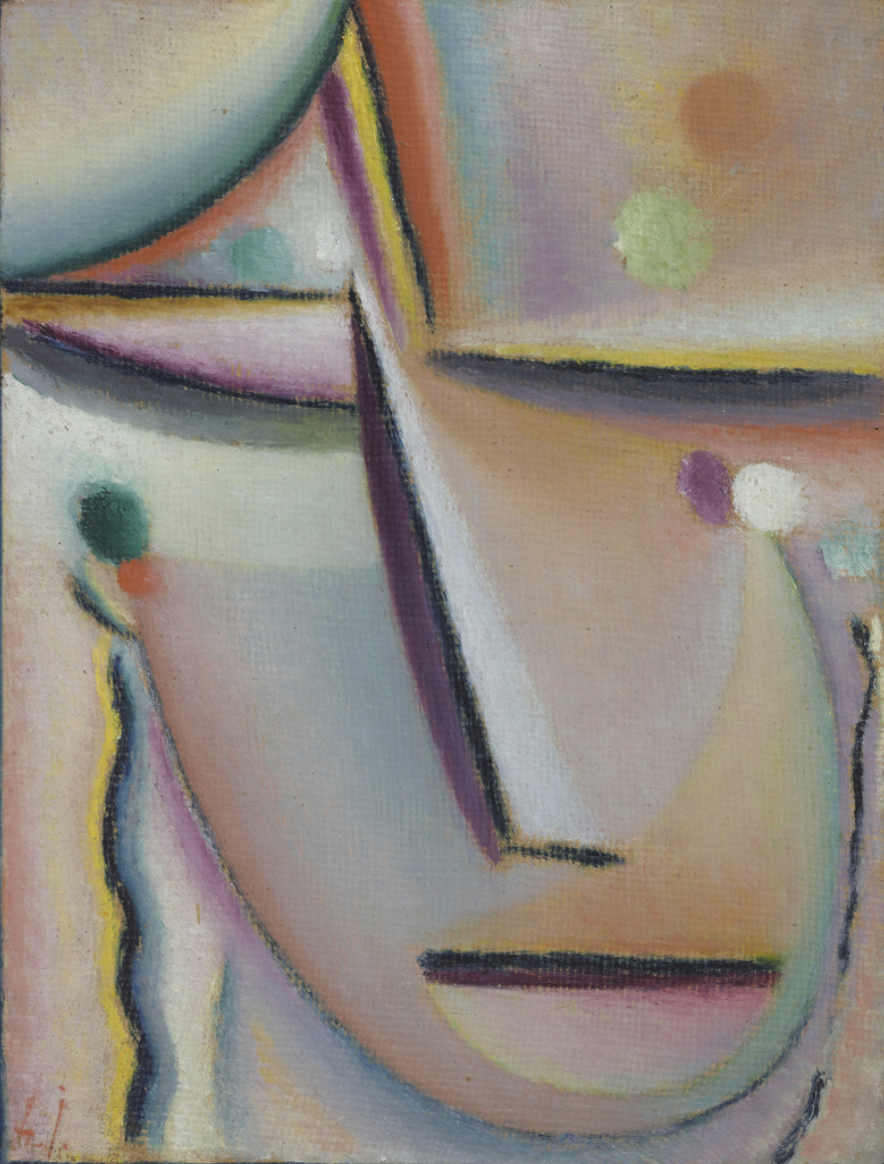

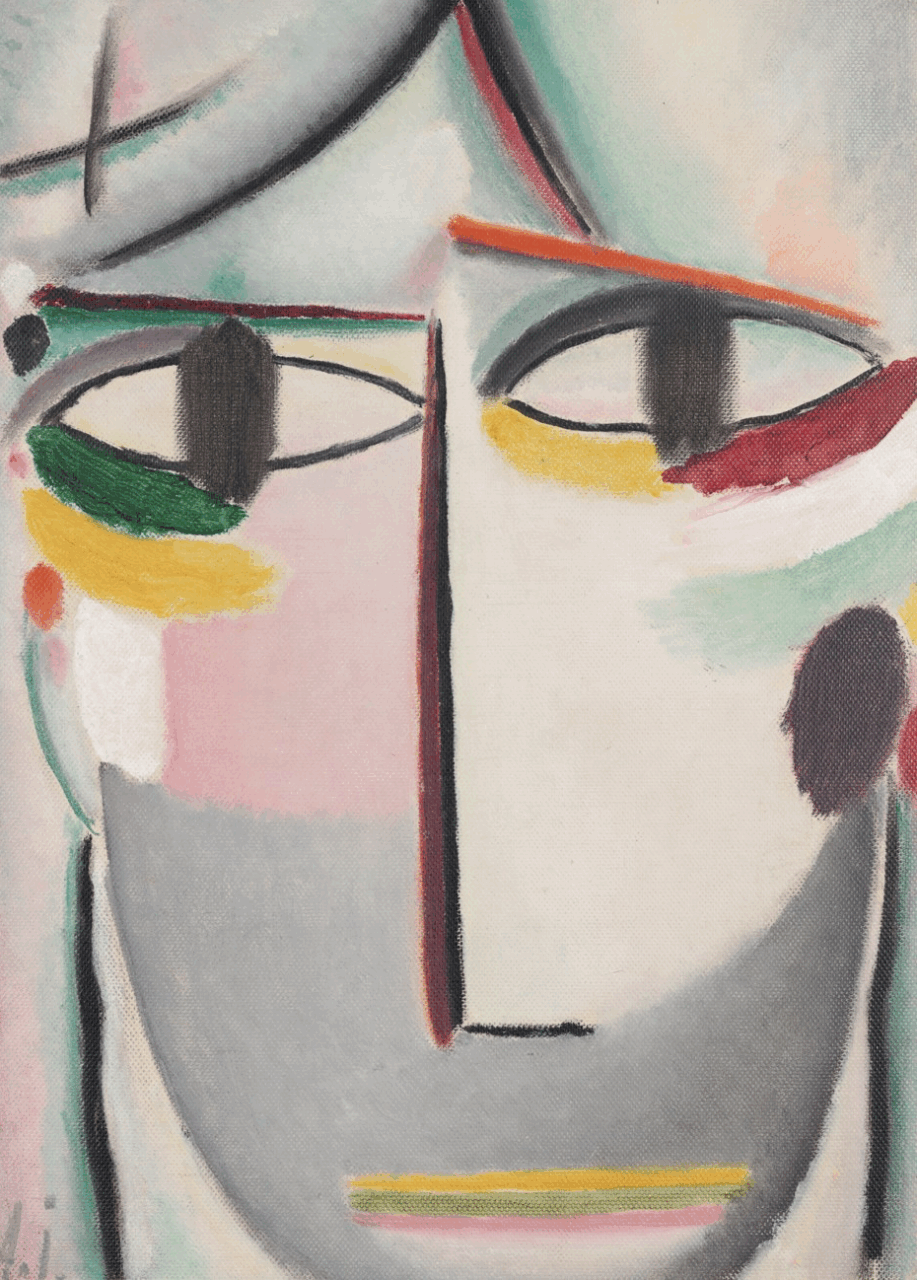

Each painting centers on an abstracted face—frontal, iconic, and architecturally structured—that recurs and evolves across the triptych. One of the most striking iconographic elements is the presence of a second set of eyes, which gradually descends from one painting to the next: from the forehead in the first, to eye level in the second, to the lower part of the face in the third. This subtle yet powerful motif serves as a visual metaphor for a shift in consciousness—from mental activity to embodied awareness, from external observation to inner perception.

Savior’s Face and Meditations

This approach places Millei in rich dialogue with early 20th-century expressive painting, particularly the work of Alexej von Jawlensky. In works like Savior’s Face and his later Meditations, Jawlensky moved away from naturalistic portraiture, transforming the face into a site of spiritual projection.

His images depict not individuals, but inner states of being—rhythmically organized, formally reduced, and suffused with a sense of stillness. While Jawlensky sought to make the divine in the human visible through repetition and color, Millei creates a secular but no less transcendent space of experience. His paintings do not speak of salvation but of awareness. The use of color in Millei’s cycle also resonates with Jawlensky’s notion of “soul chords.”

Between subject and symbol

The first painting glows with vibrating yellows and bright greens—visual equivalents of mental clarity and alertness. The central work, dominated by muted greys and earthy greens, evokes a state of grounded balance. The final painting descends into deep blues and purples, tones traditionally associated with mysticism, introspection, and silence. Here, color is not a decorative element but an integral part of the cycle’s spiritual dramaturgy.

Iconographically, Millei draws on a language of clarity and archetype. His faces do not portray individuals but suggest mythic or universal presence. Their frontal symmetry, minimalist expressions, and the symbolic presence of a second set of eyes recall sacred image traditions, yet without invoking specific religious narratives. These are not saints or saviors, but reflective surfaces for the viewer—mirrors of mental states, floating masks between subject and symbol.

reduction, symbolic resonance and emotional intensity

The formal vocabulary—circles, curves, bold outlines—generates a gestural rhythm that breathes vitality into the structural rigor. Meditation in Three Acts is not merely a reflection on consciousness; it is a painterly embodiment of it.

The cycle positions itself as a contemporary continuation of the expressionist portrait tradition, taking up Jawlensky’s quest for “inner form” and rearticulating it for the 21st century. No longer the divine in the human, but the invisible within the visible becomes the focus. In this rare synthesis of formal reduction, symbolic resonance, and emotional intensity, Millei achieves a work of lasting importance. This is not a cycle about meditation—it is a meditation, rendered in powerful visual form.

G-ALLERY · Walter-Benjamin-Platz 1 · Berlin 10629 · Germany

You must be logged in to post a comment.